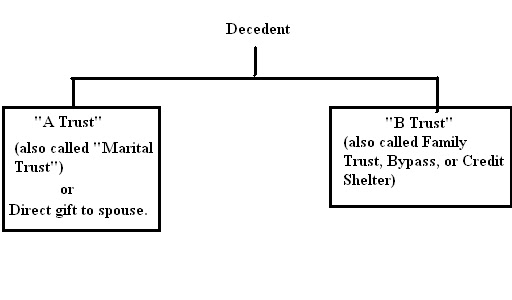

The A-B Trust works like this: the couple divides their assets equally, and each of them creates a revocable trust to hold their share of the assets. When one of them dies, the deceased person's trust splits into two components:

The first is traditionally called the "B Trust." In my office, we call it the "Family Trust," and other draftsmen may call it the "Credit Shelter" or "Bypass" trust. A "formula clause" in the trust instrument allocates assets to the B/Family/Credit Shelter/Bypass Trust equal to the maximum amount that can be protected from the federal estate tax by the deceased spouse's unified credit. This trust is taxable, but the tax is "paid" by the unified credit, so there's no tax due on this part.

Anything left over usually goes to what is traditionally called the "A Trust." We call it the "Marital Trust" in my office; I've also seen it called the "Marital Deduction Trust." The "A Trust" is designed to qualify for the marital deduction, so there is also no tax due on this part. The "price" of the marital deduction is that any property left in the "A" trust will be part of the spouse's gross estate at the second death.

There are a couple of variations on this arrangement that you should be aware of:

- If, instead of a trust, we simply distribute the assets in the "A" component directly to the surviving spouse, the tax result is exactly the same: deduction and no tax at the first death, remaining property in the gross estate on the second death.

- If the surviving spouse is not a U.S. citizen, the "A" component will be a "qualified domestic trust."

Why do we do this? There are two tax-planning reasons.

First, it ensures that we make use of the first spouse's unified credit on the first death. Up until last December, the unified credit was not transferable between individuals, so if you didn't use up the first spouse's credit when he died, it was lost forever. The 2010 tax act made unused credits "portable" between spouses, which would eliminate much of the tax reason for A-B trust arrangements--except that the 2010 tax act "sunsets" at the end of 2012, and, unless Congress amends the tax code and the President signs the amending bill into law, there will be no portability on January 1, 2013. Until we know for sure that we'll still have portability after the ball drops on New Year's Eve 2012, I am not relying on it in the estate plans I am drafting for my clients.

The second tax effect is that whatever estate taxes are paid on the couple's assets, they aren't paid until the second death. This gives the family the benefit of the time value of the money that would otherwise be paid in taxes on the first death.

Because the "A" trust has to qualify for the marital deduction, the surviving spouse is the only beneficiary while he or she is living, and the trust must pay out all of its income at least annually. The "B" trust can be anything you want. In most instances, the surviving spouse is a beneficiary, but the children or others can also be beneficiaries. The spouse's interest in the "B" trust can be more restricted than that in the "A" trust, since it need not be qualified for the marital deduction. In some situations ("blended" families in particular) the "B" component goes directly to the children or later generations on the first death, either outright or in trust.

No comments:

Post a Comment