As I'd mentioned in the discussion of the Rule Against Perpetuities, quite a few states have replaced or supplemented the Rule's complicated and counter-intuitive limit on the duration of a private trust with a fixed term of years. In Florida, for example, a contingent interest is valid if it vests (becomes certain) within 90 years, or within the traditional "life plus 21 years" period of the Rule. In Wyoming, they've replaced the Rule with a rather impressive fixed time limit. Regardless of when its contingent interests vest, a private trust governed by Wyoming law cannot last more than 1,000 years!

In some other states, of which Ohio is one, a trust can "opt out" of the Rule so long as the trustee has an unrestricted power to sell trust assets. (The power of sale means you don't have to worry about the problem that inspired the Rule in the first place: unresolved contingent interests interfering with the free transferability of property.) In other words, an Ohio trust can last, if you so desire, until the Second Coming, or until the sun swells up into a red giant, or until whatever other future event constitutes "the end of the world" in your personal belief system..

This has led to the development of what is commonly called a "dynasty trust." A dynasty trust is a trust for the benefit of one's descendants which has either a very long period (200 years or more) or no fixed termination date at all. The trustee has discretion to make distributions to any of the grantor's descendants from time to time in whatever amounts the trustee finds to be appropriate, and the trust may contain language further directing or restricting the trustee's exercise of discretion.

The trust is funded with an amount equal to what can be protected from the federal generation-skipping transfers tax by the use of the grantor's available GST exemption. It's possible for multiple grantors, such as a husband and wife or a group of siblings, to make contributions to the same trust and thus "pool" their GST exemptions. The grantor either uses up part of her unified credit, or pays the necessary gift or estate tax. The effect of the dynasty trust is to place the trust property beyond the reach of the federal wealth transfer tax system for as long as the trust lasts--the transfer subject to gift or estate tax occurs when the trust is created. Because we've used GST exemption to protect the assets of the trust from GST upon funding, it doesn't matter whether it's a "direct skip" right now or whether there are going to be "taxable distributions" and a "taxable termination" somewhere down the road.

This makes the dynasty trust a particularly good vehicle for protecting family business assets from future transfer taxes. Through the end of 2012, every individual has a $5 million GST exemption and a unified credit equal to the tax on $5 million, allowing for some spectacularly large dynasty trusts to be created--provided that you have assets in those amounts and can afford to give away that much.

Drafting a trust like this is an interesting exercise. The client will often want to give the trustee some guidance on what distributions would or would not be appropriate; my job is to put this down on paper in a way that accurately captures the client's intent while (we hope!) still being understandable to some future bank trust officer 500 years from now and being sufficiently flexible to allow that future trust officer to adapt to several centuries' worth of cultural and tax law changes.

This blog will discuss estate planning issues, tax laws, and the design of trusts and other estate planning documents.

Thursday, October 6, 2011

Monday, October 3, 2011

The Rule Against Perpetuities

The Rule Against Perpetuities is an old doctrine from the English common law which limits the duration of a private (noncharitable) trust. The most widely accepted statement of the Rule comes from Professor John Chipman Gray's classic 1886 treatise on the subject:

The Rule applies to contingent interests--that is, where the question of whether you get anything from the will or trust depends on some future event. An example would be a trust distribution where Alice receives the trust income for life, and when Alice dies, it goes to the children of Alice who are then living. We don't know if any particular one of Alice's children will get anything from the trust until either Alice or that child dies. Alice's children are therefore what we call "contingent beneficiaries." (Alice is a "vested beneficiary.")

To really, really, really (over)simplify it, the Rule requires that the interests of all contingent beneficiaries be resolved--that is, we know for sure if they'll get anything or not--before the end of a "measuring life"--the life of some person who was living when the trust was created--plus 21 years. In the example I gave in the previous paragraph, we have no problem. Alice could be our "measuring life," and when Alice dies we will know which of her children outlived her, and therefore who gets the trust property, well within the Rule's time limit. A trust with a more complex future distribution involving generations yet unborn could, however, very easily crash into the Rule. In order to avoid violating the Rule, a trust couldn't attempt to reach too far into the future.

The original purpose of the Rule was to allow for the free transfer of property. If a piece of land--which was the primary source of wealth back in the 1600s when the Rule got started--had too many contingent interests, it became impossible to transfer it because either you couldn't identify all the dozens of people who might have an interest in the land, or you couldn't find all of them, or you couldn't get them all to agree to sell the land, or you couldn't figure out how to split up the proceeds afterward, or some combination of all that.

In a modern trust with contingent interests, this is not an issue because the trustee, the sole owner of all the trust's assets, will have the power to sell those assets at any time. Even though the problem the Rule was attempting to solve wasn't a problem any more, the Rule still applied to modern day trusts. In recent years, however, most state legislatures have overridden the Rule with a statute that either replaces the "life in being plus 21" period with a fixed time limit, or allows a trust to ignore the Rule completely. We'll talk about some planning arrangements that take advantage of that change in the next post.

If you'd like to learn more about the Rule Against Perpetuities and want to have some fun doing it, I recommend you read three delightful law review articles written by Professor W. Barton Leach (1900-1971): "Perpetuities in a Nutshell" (1938), "Perpetuities in the Atomic Age: The Sperm Bank and the Fertile Decedent" (1962), and "Perpetuities: the Nutshell Revisited" (1965).

No interest is good unless it must vest, if at all, not later than twenty-one years after the death of some life in being at the creation of the interest.If you're not quite sure what that means, don't feel bad. It took Professor Gray 496 pages to explain the Rule and its application to lawyers who were already familiar with the subtleties of property law. The complexities were such that the Supreme Court of California, in a 1961 case, ruled that it was not malpractice if a lawyer drafted a will that violated the Rule because the Rule Against Perpetuities was too difficult to master!

The Rule applies to contingent interests--that is, where the question of whether you get anything from the will or trust depends on some future event. An example would be a trust distribution where Alice receives the trust income for life, and when Alice dies, it goes to the children of Alice who are then living. We don't know if any particular one of Alice's children will get anything from the trust until either Alice or that child dies. Alice's children are therefore what we call "contingent beneficiaries." (Alice is a "vested beneficiary.")

To really, really, really (over)simplify it, the Rule requires that the interests of all contingent beneficiaries be resolved--that is, we know for sure if they'll get anything or not--before the end of a "measuring life"--the life of some person who was living when the trust was created--plus 21 years. In the example I gave in the previous paragraph, we have no problem. Alice could be our "measuring life," and when Alice dies we will know which of her children outlived her, and therefore who gets the trust property, well within the Rule's time limit. A trust with a more complex future distribution involving generations yet unborn could, however, very easily crash into the Rule. In order to avoid violating the Rule, a trust couldn't attempt to reach too far into the future.

The original purpose of the Rule was to allow for the free transfer of property. If a piece of land--which was the primary source of wealth back in the 1600s when the Rule got started--had too many contingent interests, it became impossible to transfer it because either you couldn't identify all the dozens of people who might have an interest in the land, or you couldn't find all of them, or you couldn't get them all to agree to sell the land, or you couldn't figure out how to split up the proceeds afterward, or some combination of all that.

In a modern trust with contingent interests, this is not an issue because the trustee, the sole owner of all the trust's assets, will have the power to sell those assets at any time. Even though the problem the Rule was attempting to solve wasn't a problem any more, the Rule still applied to modern day trusts. In recent years, however, most state legislatures have overridden the Rule with a statute that either replaces the "life in being plus 21" period with a fixed time limit, or allows a trust to ignore the Rule completely. We'll talk about some planning arrangements that take advantage of that change in the next post.

If you'd like to learn more about the Rule Against Perpetuities and want to have some fun doing it, I recommend you read three delightful law review articles written by Professor W. Barton Leach (1900-1971): "Perpetuities in a Nutshell" (1938), "Perpetuities in the Atomic Age: The Sperm Bank and the Fertile Decedent" (1962), and "Perpetuities: the Nutshell Revisited" (1965).

Friday, September 30, 2011

Federal Estate and Gift Taxes -- Generation Skipping Taxes and How They Affect Trust Design

In the previous post, we took a quick overview of the generation-skipping transfers tax, "affectionately" known as the "GST." This is the tax that's imposed, in addition to the federal estate or gift tax, on any "generation-skipping transfer." A "generation-skipping transfer" (sometimes called a "skip") is any transfer, at death or by gift, to a "skip person." To illustrate what a "skip person" is, let's use the family tree from the last post, with a slight modification:

Grandma

|

|

Junior

|

|

Skippy

|

|

Skippy II

Grandma is the person who's going to be making the transfer. Assuming all of these people are living on the date of the transfer, Skippy and Skippy II would be "skip persons" and Junior would be a "non-skip person"--yes, that's the official term from the tax code. A gift to Skippy or Skippy II would be a "generation-skipping transfer," and will be subject to the GST unless the annual exclusion applies or Grandma has GST exemption she can allocate to the transfer. A transfer to Junior is not a skip, and will not be subject to the GST. (If Junior dies, and then Grandma makes a transfer to Skippy, that will not be a skip because there is no living person in the generation between them, and the GST won't apply--but transfers to Skippy II will still be skips subject to GST.)

So far, I've been talking about outright gifts. If the gifts are made to a trust, the question of whether they're skips or not is determined by looking at the beneficiaries of the trust. A gift to a trust for the benefit of Skippy will be a skip because Skippy is a skip person. A trust for the benefit of Skippy and Skippy II--same result, because all of the beneficiaries are skip persons. All of these transfers are called "direct skips," and if there's any GST to be paid, it's paid when the transfer is made.

Now for the tricky part: what about a trust for the benefit of Junior, Skippy, and Skippy II? Let's assume for purposes of the example that the trustee can make distributions to any one or more of these three people in its discretion. A trust like this might be seen where Junior is the "gray sheep" of the family.

In this case, when Grandma puts assets into the trust, we don't know if the transfer is a skip yet because we don't know if any particular property in the trust will be distributed out to a skip person (Skippy and Skippy II) or a non-skip person (Junior). If the trust makes any distribution to Junior, those are not skips, and there's no GST. Any distributions to Skippy or Skippy II are "taxable distributions" on which a GST will have to be paid at the time of distribution unless Grandma allocated GST exemption to the trust back when she created it.

What happens when Junior dies? As of that moment, we know for a certainty that all future distributions will be to the skip persons. Junior's death is therefore a "taxable termination"--it's called that because the interests of all non-skip persons in the trust have terminated--and is the occasion for assessing the GST against all of the remaining trust property--again, unless Grandma allocated GST exemption to the trust back when she created it.

In other words, a transfer to one of your children which is held in trust for life, with final distribution to your grandchildren, may subject the trust property to the GST. Therefore, it's necessary to allocate GST exemption to the trust when the trust is created; this is done on the relevant estate tax or gift tax return. If you don't have enough GST exemption to cover the entire transfer, the trust has to be designed so that the non-exempt part is included in your child's estate so that it's taxed there instead of being hammered by the GST.

Monday, September 26, 2011

Federal Estate and Gift Taxes -- the Generation Skipping Transfers Tax

The generation-skipping transfers tax, or "GST" for short, is perhaps the hardest-hitting element of the federal wealth transfer tax system. For purposes of illustration, let's use a very simple family tree:

To begin, imagine that it's before 1976, when the first version of the GST was enacted. (It was replaced in 1986 with the arrangement we have today.) By virtue of his place in the family business and/or earlier gifts from Grandma, Junior is independently wealthy. Anything that Grandma leaves to him at death will simply get added to Junior's gross estate and taxed again at Junior's passing. What people in Grandma's position often did was to create a trust for Skippy and the other grandkids, and perhaps also later generations, and thus "skip" taxation in Junior's generation. The trust usually could reach no farther than the grandchildren's generation because of something called the Rule Against Perpetuities, which we'll discuss another time.

As we've noted in earlier posts, one of the baseline policies of the gift and estate tax system is to tax accumulated wealth once per generation, and generation skipping transfers like these cut that down to once every other generation. Because most people would only do this if Junior was well provided-for, these "generation-skipping trusts" were a strategy only a very very high net worth family could make use of--so that the estate and gift taxes actually fell harder on those who were wealthy enough to pay estate taxes, but not wealthy enough to play at generation skipping.

To redress this flaw and discourage generation skipping transfers, Congress enacted the GST. The GST is imposed, in addition to the estate or gift tax, on any transfer to a "skip person." There's a complex definition of a "skip person" in the tax code, but what it boils down to is that, in the example above, Skippy is a "skip person" if Junior is living on the date of the transfer. If Junior dies, and then Grandma makes the transfer to Skippy, it's not a generation skipping transfer and the GST does not apply.

What makes the GST hit so hard is the rate of tax: it's equal to the highest estate tax rate then in effect. In 1986, when the modern version of the GST entered the tax code, that top rate was 55%--so it was possible for a generation-skipping transfer to be taxed at a combined 110% (up to 55% estate/gift tax + 55% GST). The purpose of this was not to collect a 110% tax so much as it was to make large generation-skipping transfers so uneconomical that no one would want to do them.

Well, maybe not all generation-skipping transfers. Not wanting tax policy to interfere too much with the time-honored tradition of doting on grandchildren, Congress also provided that the GST does not apply to most annual exclusion gifts, and gave every person a $1 million GST exemption. The exemption let each person transfer a total of $1 million to the grandkids (and other skip persons) before the GST kicked in. (There was also a $2 million-per-grandchild temporary exemption which expired in 1989--named the "Gallo provision" in honor of the high net-worth family which "suggested" it to their Congressional representatives.)

Under the 2001 tax act ("the Bush tax cuts"), the GST exemption increased in parallel with the exemption equivalent provided by the estate and gift tax unified credit, so that it reached $3.5 million in 2009. During the "estate tax holiday" in 2010, there was (so we thought) no GST at all. The 2010 tax act reinstated the GST retroactive to January 1, 2010, but at a 0% rate--so if you made a generation-skipping transfer before the tax was retroactively re-imposed, you didn't get hit with a surprise tax assessment. For 2011 and 2012, the GST exemption is $5 million. Unless Congress acts before the end of next year, the GST exemption will "snap back" to $1 million on January 1, 2013, as part of what the media calls the "expiration" of the "Bush tax cuts."

You may think that the GST is a problem only for the super wealthy, but it can affect people of relatively modest means. A trust for your "gray sheep" child which holds the assets for the child's life, then distributes to that child's offspring afterward, is a generation-skipping transfer that is subject to the tax unless there is sufficient GST exemption to cover it. We'll talk about how the GST affects trust design, and some of the "work-arounds" that have been developed to counter it, in future postings.

Grandma

|

|

Junior

|

|

Skippy

To begin, imagine that it's before 1976, when the first version of the GST was enacted. (It was replaced in 1986 with the arrangement we have today.) By virtue of his place in the family business and/or earlier gifts from Grandma, Junior is independently wealthy. Anything that Grandma leaves to him at death will simply get added to Junior's gross estate and taxed again at Junior's passing. What people in Grandma's position often did was to create a trust for Skippy and the other grandkids, and perhaps also later generations, and thus "skip" taxation in Junior's generation. The trust usually could reach no farther than the grandchildren's generation because of something called the Rule Against Perpetuities, which we'll discuss another time.

As we've noted in earlier posts, one of the baseline policies of the gift and estate tax system is to tax accumulated wealth once per generation, and generation skipping transfers like these cut that down to once every other generation. Because most people would only do this if Junior was well provided-for, these "generation-skipping trusts" were a strategy only a very very high net worth family could make use of--so that the estate and gift taxes actually fell harder on those who were wealthy enough to pay estate taxes, but not wealthy enough to play at generation skipping.

To redress this flaw and discourage generation skipping transfers, Congress enacted the GST. The GST is imposed, in addition to the estate or gift tax, on any transfer to a "skip person." There's a complex definition of a "skip person" in the tax code, but what it boils down to is that, in the example above, Skippy is a "skip person" if Junior is living on the date of the transfer. If Junior dies, and then Grandma makes the transfer to Skippy, it's not a generation skipping transfer and the GST does not apply.

What makes the GST hit so hard is the rate of tax: it's equal to the highest estate tax rate then in effect. In 1986, when the modern version of the GST entered the tax code, that top rate was 55%--so it was possible for a generation-skipping transfer to be taxed at a combined 110% (up to 55% estate/gift tax + 55% GST). The purpose of this was not to collect a 110% tax so much as it was to make large generation-skipping transfers so uneconomical that no one would want to do them.

Well, maybe not all generation-skipping transfers. Not wanting tax policy to interfere too much with the time-honored tradition of doting on grandchildren, Congress also provided that the GST does not apply to most annual exclusion gifts, and gave every person a $1 million GST exemption. The exemption let each person transfer a total of $1 million to the grandkids (and other skip persons) before the GST kicked in. (There was also a $2 million-per-grandchild temporary exemption which expired in 1989--named the "Gallo provision" in honor of the high net-worth family which "suggested" it to their Congressional representatives.)

Under the 2001 tax act ("the Bush tax cuts"), the GST exemption increased in parallel with the exemption equivalent provided by the estate and gift tax unified credit, so that it reached $3.5 million in 2009. During the "estate tax holiday" in 2010, there was (so we thought) no GST at all. The 2010 tax act reinstated the GST retroactive to January 1, 2010, but at a 0% rate--so if you made a generation-skipping transfer before the tax was retroactively re-imposed, you didn't get hit with a surprise tax assessment. For 2011 and 2012, the GST exemption is $5 million. Unless Congress acts before the end of next year, the GST exemption will "snap back" to $1 million on January 1, 2013, as part of what the media calls the "expiration" of the "Bush tax cuts."

You may think that the GST is a problem only for the super wealthy, but it can affect people of relatively modest means. A trust for your "gray sheep" child which holds the assets for the child's life, then distributes to that child's offspring afterward, is a generation-skipping transfer that is subject to the tax unless there is sufficient GST exemption to cover it. We'll talk about how the GST affects trust design, and some of the "work-arounds" that have been developed to counter it, in future postings.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

E-Mail and Attorney-Client Confidentiality

I plan to do a future post on attorney-client privilege and confidentiality issues in estate planning. While you're waiting for that, I'll refer you to an interesting article on confidentiality issues with the use of electronic mail published at lawyerist.com.

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

The Gray Sheep

What's a "gray sheep?"

You all know what a "black sheep" is, in the metaphorical sense: the black sheep is the child or grandchild who has turned out wrong, done something stupid or illegal or immoral (or some combination thereof) that has brought shame and disgrace to the family. When it comes time to do the estate planning, the black sheep is the one who doesn't get anything--or, at best, gets some token distribution on the condition that they don't contest the will or the trust.

A gray sheep is a beneficiary who isn't quite bad enough to be a black sheep. He may have done something stupid or illegal or immoral (or some combination thereof), but whatever it was it wasn't quite bad enough to justify cutting him out completely. There's a second breed of gray sheep, the one who has a chemical dependency problem, massive debts, a spouse that can't be trusted, or a simple lack of good sense. The client I'm drafting the documents for still wants to give something to the gray sheep, but not directly, not in a way that puts them in control of the wealth.

As you might have guessed, gifts to gray sheep are going to be held in trust. The exact terms will vary based on the circumstances, including the amount of money or property at stake, and how gray (metaphorically) the gray sheep is and how she got that way. Some of the terms used in gray sheep trusts include:

You all know what a "black sheep" is, in the metaphorical sense: the black sheep is the child or grandchild who has turned out wrong, done something stupid or illegal or immoral (or some combination thereof) that has brought shame and disgrace to the family. When it comes time to do the estate planning, the black sheep is the one who doesn't get anything--or, at best, gets some token distribution on the condition that they don't contest the will or the trust.

A gray sheep is a beneficiary who isn't quite bad enough to be a black sheep. He may have done something stupid or illegal or immoral (or some combination thereof), but whatever it was it wasn't quite bad enough to justify cutting him out completely. There's a second breed of gray sheep, the one who has a chemical dependency problem, massive debts, a spouse that can't be trusted, or a simple lack of good sense. The client I'm drafting the documents for still wants to give something to the gray sheep, but not directly, not in a way that puts them in control of the wealth.

As you might have guessed, gifts to gray sheep are going to be held in trust. The exact terms will vary based on the circumstances, including the amount of money or property at stake, and how gray (metaphorically) the gray sheep is and how she got that way. Some of the terms used in gray sheep trusts include:

- Holding the principal in trust until some advanced age (50, 55, 60, 65 even) or for the gray sheep's life. (A lifetime trust with remainder to grandchildren presents some issues with the generation-skipping transfers tax that we will go into in a future installment).

- Making distributions out of the trust discretionary subject to an "ascertainable standard" such as "health, maintenance, education, and support."

- Making distributions "wholly discretionary." Under the Ohio Trust Code, a "wholly discretionary" trust is not subject to the claims of the gray sheep's creditors-making wholly discretionary trusts extremely useful for gray sheep with creditor problems.

- The discretionary distributions may be further subject to the approval of a trust advisor.

- The distributions, even though they may be discretionary or even wholly discretionary, may be capped off at a certain amount per year, or limited to expenditures for certain purposes only.

- If the gray sheep's problem is one of motivation, the trustee could be directed to make distributions in an amount determined with reference to the gray sheep's earned income. The harder you work, the more the trust gives you.

- Distributions could be made contingent on certain accomplishments, or on refraining from certain specified bad behavior. I have drafted at least two trusts where the beneficiary's right to further distributions was contingent upon passing random drug tests. If the beneficiary failed, the trustee was restricted to making distributions only to pay for rehab treatment.

Monday, September 19, 2011

Federal Estate and Gift Taxes -- the Annual Exclusion

The purpose of the gift tax is to prevent people from "sneaking" around the estate tax by giving away assets before death. There's no official definition of a gift, but the general understanding is that a gift is any transfer of property that makes your estate smaller. The gift tax part of the Internal Revenue Code expressly says that it is not a "gift" to pay someone's medical or educational expenses. There's no exemption for everyday living expenses, but as far as I know the IRS has never tried to characterize basic consumption, such as the cost of feeding and housing your kids, as a taxable gift.

Even with those exceptions, every Christmas present and birthday card would still be a taxable gift, and only the most miserly among us would not be required to file Form 709 every year. To avoid the resulting absurdity, Congress wrote in something called the "annual exclusion." It's presently $13,000 per recipient per year, and that number adjusts for inflation every so often. Put simply, the first $13,000 in gifts you make to a person in any one year are "freebies," ignored for gift tax purposes. If you have two children, you can give each of then $13,000 and not owe any gift taxes. A married couple can combine their exclusions (something called "gift splitting") and give $26,000 per year to each recipient tax free--it's considered to come equally from both, no matter who wrote the check or made the transfer.

Now here's the tricky part: the annual exclusion only applies to a "present interest" gift; that is, something that the recipient can enjoy immediately. A gift of a right to receive something in the future, or a gift in trust that won't be distributed immediately, is not a present interest, and doesn't get the benefit of the annual exclusion.

It's often not a good idea to make a substantial gift outright to a young person, or an adult with maturity or creditor problems. You'd want to hold the property in trust so the beneficiary can't mishandle it--and, in the case of a minor, so you don't have to establish a guardianship to hold the property. Section 2503(c) of the IRC sets out a specific exception for gifts in trust to a minor, but section 2503 trusts have to terminate when the beneficiary reaches age 21. 21 is the traditional age of majority, but not always a comfortable age to be distributing substantial wealth to someone.

So does that mean that if you want to make a gift in trust to, say, age 30 you can't use the annual exclusion? No; there's a work-around called a "Crummey power," named after the United States Tax Court case which validated the tactic. The trust will give the beneficiary a legal right to withdraw property as soon as it's added to the trust, but that right expires one month after the date the beneficiary (or, if a minor, her parent or guardian) is advised that a contribution has been made. That's a present enough present interest to qualify the gift for the annual exclusion. As you might expect, this is something we use a lot in my business.

Even with those exceptions, every Christmas present and birthday card would still be a taxable gift, and only the most miserly among us would not be required to file Form 709 every year. To avoid the resulting absurdity, Congress wrote in something called the "annual exclusion." It's presently $13,000 per recipient per year, and that number adjusts for inflation every so often. Put simply, the first $13,000 in gifts you make to a person in any one year are "freebies," ignored for gift tax purposes. If you have two children, you can give each of then $13,000 and not owe any gift taxes. A married couple can combine their exclusions (something called "gift splitting") and give $26,000 per year to each recipient tax free--it's considered to come equally from both, no matter who wrote the check or made the transfer.

Now here's the tricky part: the annual exclusion only applies to a "present interest" gift; that is, something that the recipient can enjoy immediately. A gift of a right to receive something in the future, or a gift in trust that won't be distributed immediately, is not a present interest, and doesn't get the benefit of the annual exclusion.

It's often not a good idea to make a substantial gift outright to a young person, or an adult with maturity or creditor problems. You'd want to hold the property in trust so the beneficiary can't mishandle it--and, in the case of a minor, so you don't have to establish a guardianship to hold the property. Section 2503(c) of the IRC sets out a specific exception for gifts in trust to a minor, but section 2503 trusts have to terminate when the beneficiary reaches age 21. 21 is the traditional age of majority, but not always a comfortable age to be distributing substantial wealth to someone.

So does that mean that if you want to make a gift in trust to, say, age 30 you can't use the annual exclusion? No; there's a work-around called a "Crummey power," named after the United States Tax Court case which validated the tactic. The trust will give the beneficiary a legal right to withdraw property as soon as it's added to the trust, but that right expires one month after the date the beneficiary (or, if a minor, her parent or guardian) is advised that a contribution has been made. That's a present enough present interest to qualify the gift for the annual exclusion. As you might expect, this is something we use a lot in my business.

Friday, September 16, 2011

Estate Planning for Guardians

The title of this post is also the topic of a CLE presentation I'm giving next Tuesday in Cleveland. Adult guardianships are something I deal with pretty regularly, and the intersection between estate planning and guardianship law is an interesting subject (at least to me).

The law presumes that adults are competent. In a sense, "competency" is a synonym for "autonomy." A competent adult is free to use or dispose of his or her property in whatever manner he or she sees fit—subject to certain constraints which we won't go into right now.

A person is "incompetent" if, as the statute says, he or she is

The guardianship statutes explicitly state that the guardian cannot make or change a will, and the courts interpret that to prohibit the guardian from making any kind of change to a trust or other estate planning arrangements. A guardian can obtain authority to make lifetime gifts, but only if the court finds that the ward would have wanted to make the gift if competent.

The law presumes that adults are competent. In a sense, "competency" is a synonym for "autonomy." A competent adult is free to use or dispose of his or her property in whatever manner he or she sees fit—subject to certain constraints which we won't go into right now.

A person is "incompetent" if, as the statute says, he or she is

...so mentally impaired as a result of a mental or physical illness or disability, or mental retardation, or as a result of chronic substance abuse, that the person is incapable of taking proper care of the person's self or property or fails to provide for the person's family or other persons for whom the person is charged by law to provide....An incompetent person is legally unable to act for themselves. Unless he or she has appointed an agent under a durable power of attorney or placed property in trust, it will be necessary to appoint a guardian to manage the individual's property. Guardians have most of the same powers over property as their ward would have if competent, but everything the guardian does is subject to court approval in advance.

The guardianship statutes explicitly state that the guardian cannot make or change a will, and the courts interpret that to prohibit the guardian from making any kind of change to a trust or other estate planning arrangements. A guardian can obtain authority to make lifetime gifts, but only if the court finds that the ward would have wanted to make the gift if competent.

Thursday, September 15, 2011

The Classic A-B Trust Estate Plan

In previous articles, I've discussed the basics of the federal estate tax, including the unified credit and the unlimited marital deduction. In this installment, I'm going to explain how a married couple can use the marital deduction and the unified credit in the most efficient manner. Under the estate tax as it presently stands, a couple can transmit up to $10 million to the next generation without paying any federal estate tax, and deferring any estate tax at all to the second death. This is accomplished by the use of an estate planning tactic known as an "A-B Trust."

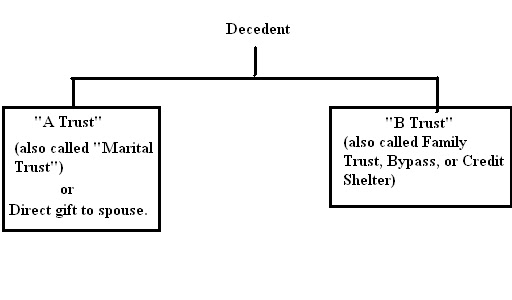

The A-B Trust works like this: the couple divides their assets equally, and each of them creates a revocable trust to hold their share of the assets. When one of them dies, the deceased person's trust splits into two components:

The first is traditionally called the "B Trust." In my office, we call it the "Family Trust," and other draftsmen may call it the "Credit Shelter" or "Bypass" trust. A "formula clause" in the trust instrument allocates assets to the B/Family/Credit Shelter/Bypass Trust equal to the maximum amount that can be protected from the federal estate tax by the deceased spouse's unified credit. This trust is taxable, but the tax is "paid" by the unified credit, so there's no tax due on this part.

Anything left over usually goes to what is traditionally called the "A Trust." We call it the "Marital Trust" in my office; I've also seen it called the "Marital Deduction Trust." The "A Trust" is designed to qualify for the marital deduction, so there is also no tax due on this part. The "price" of the marital deduction is that any property left in the "A" trust will be part of the spouse's gross estate at the second death.

There are a couple of variations on this arrangement that you should be aware of:

Why do we do this? There are two tax-planning reasons.

First, it ensures that we make use of the first spouse's unified credit on the first death. Up until last December, the unified credit was not transferable between individuals, so if you didn't use up the first spouse's credit when he died, it was lost forever. The 2010 tax act made unused credits "portable" between spouses, which would eliminate much of the tax reason for A-B trust arrangements--except that the 2010 tax act "sunsets" at the end of 2012, and, unless Congress amends the tax code and the President signs the amending bill into law, there will be no portability on January 1, 2013. Until we know for sure that we'll still have portability after the ball drops on New Year's Eve 2012, I am not relying on it in the estate plans I am drafting for my clients.

The second tax effect is that whatever estate taxes are paid on the couple's assets, they aren't paid until the second death. This gives the family the benefit of the time value of the money that would otherwise be paid in taxes on the first death.

Because the "A" trust has to qualify for the marital deduction, the surviving spouse is the only beneficiary while he or she is living, and the trust must pay out all of its income at least annually. The "B" trust can be anything you want. In most instances, the surviving spouse is a beneficiary, but the children or others can also be beneficiaries. The spouse's interest in the "B" trust can be more restricted than that in the "A" trust, since it need not be qualified for the marital deduction. In some situations ("blended" families in particular) the "B" component goes directly to the children or later generations on the first death, either outright or in trust.

The A-B Trust works like this: the couple divides their assets equally, and each of them creates a revocable trust to hold their share of the assets. When one of them dies, the deceased person's trust splits into two components:

The first is traditionally called the "B Trust." In my office, we call it the "Family Trust," and other draftsmen may call it the "Credit Shelter" or "Bypass" trust. A "formula clause" in the trust instrument allocates assets to the B/Family/Credit Shelter/Bypass Trust equal to the maximum amount that can be protected from the federal estate tax by the deceased spouse's unified credit. This trust is taxable, but the tax is "paid" by the unified credit, so there's no tax due on this part.

Anything left over usually goes to what is traditionally called the "A Trust." We call it the "Marital Trust" in my office; I've also seen it called the "Marital Deduction Trust." The "A Trust" is designed to qualify for the marital deduction, so there is also no tax due on this part. The "price" of the marital deduction is that any property left in the "A" trust will be part of the spouse's gross estate at the second death.

There are a couple of variations on this arrangement that you should be aware of:

- If, instead of a trust, we simply distribute the assets in the "A" component directly to the surviving spouse, the tax result is exactly the same: deduction and no tax at the first death, remaining property in the gross estate on the second death.

- If the surviving spouse is not a U.S. citizen, the "A" component will be a "qualified domestic trust."

Why do we do this? There are two tax-planning reasons.

First, it ensures that we make use of the first spouse's unified credit on the first death. Up until last December, the unified credit was not transferable between individuals, so if you didn't use up the first spouse's credit when he died, it was lost forever. The 2010 tax act made unused credits "portable" between spouses, which would eliminate much of the tax reason for A-B trust arrangements--except that the 2010 tax act "sunsets" at the end of 2012, and, unless Congress amends the tax code and the President signs the amending bill into law, there will be no portability on January 1, 2013. Until we know for sure that we'll still have portability after the ball drops on New Year's Eve 2012, I am not relying on it in the estate plans I am drafting for my clients.

The second tax effect is that whatever estate taxes are paid on the couple's assets, they aren't paid until the second death. This gives the family the benefit of the time value of the money that would otherwise be paid in taxes on the first death.

Because the "A" trust has to qualify for the marital deduction, the surviving spouse is the only beneficiary while he or she is living, and the trust must pay out all of its income at least annually. The "B" trust can be anything you want. In most instances, the surviving spouse is a beneficiary, but the children or others can also be beneficiaries. The spouse's interest in the "B" trust can be more restricted than that in the "A" trust, since it need not be qualified for the marital deduction. In some situations ("blended" families in particular) the "B" component goes directly to the children or later generations on the first death, either outright or in trust.

Wednesday, July 27, 2011

Changes in Delaware Trust Law

Clients with complex estate planning needs, including those with significant liability exposure who need to take "asset protection" measures, will often set up their trusts in the state of Delaware, which is the home of some of the nations oldest trust companies and has a highly developed law of trusts.

Delaware has made some significant changes to its trust laws which take effect this coming Monday, August 1, 2011. The changes include improved protection from creditors for assets held in trust, and revisions to the "decanting" statute which allows a trustee to create another trust and transfer assets to it. You can read or download a detailed summary of the changes here.

Delaware has made some significant changes to its trust laws which take effect this coming Monday, August 1, 2011. The changes include improved protection from creditors for assets held in trust, and revisions to the "decanting" statute which allows a trustee to create another trust and transfer assets to it. You can read or download a detailed summary of the changes here.

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Federal Estate and Gift Taxes -- the Unified Credit, Today and Tomorrow

The federal wealth transfer taxes are imposed on any gift (with certain exceptions), and any estate, no matter how small. In order that these taxes only actually get paid by "the wealthy," everyone is given a "unified credit" against these taxes. We usually do not talk about the credit itself; rather, we refer to the "exemption equivalent," which is the amount of wealth that the credit "pays" the tax on.

When I started practicing law, and for a long time thereafter, the exemption equivalent was $600,000; that is, the credit was equal to the tax on $600,000 of lifetime gifts and/or wealth transmitted at death. Once the credit ran out, the tax rate on the 600,001st dollar was 37%, and the rate brackets topped out at 55% once you got to $3 million.

By making full use of both spouse's credits, a married couple could transmit $1.2 million to the next generation before incurring a federal tax. At the time these numbers were established, $1.2 million was a net worth that few couples could attain. After fourteen years of cumulative inflation and rising standards of living, however, the tax was starting to hit a lot of farmers, small business owners, and other upper middle class taxpayers who were rich enough, in terms of assets, to be hit by the tax, but who often weren't liquid enough to raise the cash with which to pay the tax without selling or borrowing against their main assets--the house, the farm, or the business.

The 1997 tax act.addressed this by scheduling a series of irregular increases in the unified credit that would eventually raise the exemption equivalent to $1 million. The increase was "back-loaded" so that most of it occurred in later years. By 2001, we were about halfway through the process, and the exemption equivalent was $675,000.

The 2001 tax act--which enacted what reporters, pundits, and politicians like to refer to as the "Bush tax cuts"--provided for the complete phase-out of the federal estate tax over a ten year period. The exemption equivalent for estates was increased immediately to $1 million, and scheduled to go to $1.5 million in 2004, $2 million in 2006, and $3.5 million in 2009. In 2010, the estate tax was scheduled to disappear completely. While this was going on, the top rate was decreasing from 55% to 45% in a series of irregular jumps. The exemption equivalent for lifetime gifts was capped at $1 million, and after the estate tax went out of existence there would still be a 35% tax on lifetime gifts, with a $1 million exemption equivalent.

The 2001 tax act also contained a "sunset" clause under which all the changes it worked in the tax code would be undone on January 1, 2011, which would un-repeal the estate tax and cause a return to what the 1997 tax act was working toward: an estate and gift tax with a $1 million exemption equivalent and a 55% top rate. The reason for this is because one of the rules governing the federal budget process provides that no legislation affecting revenue can be in effect for more than ten years unless it passes with at least 60 votes in the Senate. As you might remember, we had a closely-divided Senate at that time, and the 2001 tax act passed by only a small majority.

Those of us in the estate planning business expected that Congress would change things again well before 2010 so we wouldn't have that strange temporary repeal, but that didn't happen. In late 2009, there had been several bills introduced to extend the estate tax past 2009 with a $3.5 million exemption equivalent (and one that would have reduced it to $2 million!), but none of these got through the legislative process because Congress was then focused intensely on the pending "Obamacare" health care reform bill.

Consequently, there was no estate tax for nearly all of last year, but with a scheduled automatic reinstatement of the tax (and a lot of other changes to other parts of the tax code) on January 1, 2011. In December, Congress passed, and the President signed into law, legislation which prevented the sunset from taking place. For the most part, it provided that the changes to the tax code made by the 2001 tax act would continue in effect through the end of 2012--what the media, pundits, and politicians described as "an extension of the Bush tax cuts." Part of this bill reinstated the estate tax--but with a $5 million exemption equivalent, a 35% top rate, and a new "portability" provision which allows a widowed spouse to make use of any unified credit the deceased spouse did not use on his estate tax return or on lifetime gifts. This is the most taxpayer-friendly that the federal estate tax has been since 1931.

However, things may soon change for the worse. The 2010 tax act was a bundle of compromises, and one of those compromises was a provision that "sunsets" the 2010 act at the end of 2012. Unless Congress changes the tax code again before the end of next year, we will "snap back" to the 1997 version of the estate tax--an estate and gift tax with a $1 million exemption equivalent and a 55% top rate--on January 1, 2013.

There are many members of Congress who have come out in favor of making the 2010 estate tax scheme permanent. President Obama has stated on numerous occasions that he is opposed to "further extensions" of the "Bush tax cuts," which seems a pretty clear signal that he would oppose making the 2010 estate tax scheme permanent. It is probable that any legislation to address the estate tax would be introduced and debated next year--in the middle of a long and contentious national election campaign.

No one can safely predict what will happen next, and estate planning for families with small businesses and farms has gotten a lot more complicated as a result.

When I started practicing law, and for a long time thereafter, the exemption equivalent was $600,000; that is, the credit was equal to the tax on $600,000 of lifetime gifts and/or wealth transmitted at death. Once the credit ran out, the tax rate on the 600,001st dollar was 37%, and the rate brackets topped out at 55% once you got to $3 million.

By making full use of both spouse's credits, a married couple could transmit $1.2 million to the next generation before incurring a federal tax. At the time these numbers were established, $1.2 million was a net worth that few couples could attain. After fourteen years of cumulative inflation and rising standards of living, however, the tax was starting to hit a lot of farmers, small business owners, and other upper middle class taxpayers who were rich enough, in terms of assets, to be hit by the tax, but who often weren't liquid enough to raise the cash with which to pay the tax without selling or borrowing against their main assets--the house, the farm, or the business.

The 1997 tax act.addressed this by scheduling a series of irregular increases in the unified credit that would eventually raise the exemption equivalent to $1 million. The increase was "back-loaded" so that most of it occurred in later years. By 2001, we were about halfway through the process, and the exemption equivalent was $675,000.

The 2001 tax act--which enacted what reporters, pundits, and politicians like to refer to as the "Bush tax cuts"--provided for the complete phase-out of the federal estate tax over a ten year period. The exemption equivalent for estates was increased immediately to $1 million, and scheduled to go to $1.5 million in 2004, $2 million in 2006, and $3.5 million in 2009. In 2010, the estate tax was scheduled to disappear completely. While this was going on, the top rate was decreasing from 55% to 45% in a series of irregular jumps. The exemption equivalent for lifetime gifts was capped at $1 million, and after the estate tax went out of existence there would still be a 35% tax on lifetime gifts, with a $1 million exemption equivalent.

The 2001 tax act also contained a "sunset" clause under which all the changes it worked in the tax code would be undone on January 1, 2011, which would un-repeal the estate tax and cause a return to what the 1997 tax act was working toward: an estate and gift tax with a $1 million exemption equivalent and a 55% top rate. The reason for this is because one of the rules governing the federal budget process provides that no legislation affecting revenue can be in effect for more than ten years unless it passes with at least 60 votes in the Senate. As you might remember, we had a closely-divided Senate at that time, and the 2001 tax act passed by only a small majority.

Those of us in the estate planning business expected that Congress would change things again well before 2010 so we wouldn't have that strange temporary repeal, but that didn't happen. In late 2009, there had been several bills introduced to extend the estate tax past 2009 with a $3.5 million exemption equivalent (and one that would have reduced it to $2 million!), but none of these got through the legislative process because Congress was then focused intensely on the pending "Obamacare" health care reform bill.

Consequently, there was no estate tax for nearly all of last year, but with a scheduled automatic reinstatement of the tax (and a lot of other changes to other parts of the tax code) on January 1, 2011. In December, Congress passed, and the President signed into law, legislation which prevented the sunset from taking place. For the most part, it provided that the changes to the tax code made by the 2001 tax act would continue in effect through the end of 2012--what the media, pundits, and politicians described as "an extension of the Bush tax cuts." Part of this bill reinstated the estate tax--but with a $5 million exemption equivalent, a 35% top rate, and a new "portability" provision which allows a widowed spouse to make use of any unified credit the deceased spouse did not use on his estate tax return or on lifetime gifts. This is the most taxpayer-friendly that the federal estate tax has been since 1931.

However, things may soon change for the worse. The 2010 tax act was a bundle of compromises, and one of those compromises was a provision that "sunsets" the 2010 act at the end of 2012. Unless Congress changes the tax code again before the end of next year, we will "snap back" to the 1997 version of the estate tax--an estate and gift tax with a $1 million exemption equivalent and a 55% top rate--on January 1, 2013.

There are many members of Congress who have come out in favor of making the 2010 estate tax scheme permanent. President Obama has stated on numerous occasions that he is opposed to "further extensions" of the "Bush tax cuts," which seems a pretty clear signal that he would oppose making the 2010 estate tax scheme permanent. It is probable that any legislation to address the estate tax would be introduced and debated next year--in the middle of a long and contentious national election campaign.

No one can safely predict what will happen next, and estate planning for families with small businesses and farms has gotten a lot more complicated as a result.

Monday, July 11, 2011

Federal Estate and Gift Taxes -- Trusts for the Non-Citizen Spouse

As mentioned in the last installment of this series, the unlimited marital deduction is only available if your spouse is a U.S. citizen. If your spouse is not a U.S. citizen, transfers to that spouse at death will be subject to the estate tax unless you use a "qualified domestic trust," or "QDOT."

A QDOT trust must pay all of its income to the surviving spouse, and can have no other beneficiaries while the spouse is living. So far, this looks a lot like a QTIP marital deduction trust, but a QDOT is subject to additional restrictions intended to prevent the non-citizen spouse from leaving the country with the assets and thereby escaping estate taxation:

How do you prevent taxation of principal distributions? If the spouse becomes a U.S. citizen, the special QDOT restrictions and the tax on lifetime principal distributions no longer apply.

A QDOT trust must pay all of its income to the surviving spouse, and can have no other beneficiaries while the spouse is living. So far, this looks a lot like a QTIP marital deduction trust, but a QDOT is subject to additional restrictions intended to prevent the non-citizen spouse from leaving the country with the assets and thereby escaping estate taxation:

- At least one of the trustees must be an individual U.S. citizen or a U.S. trust company.

- No more than 35% of the assets of the trust may be foreign real estate.

- The U.S. trustee has the power to withhold taxes from any distribution of principal.

How do you prevent taxation of principal distributions? If the spouse becomes a U.S. citizen, the special QDOT restrictions and the tax on lifetime principal distributions no longer apply.

Friday, July 8, 2011

Federal Estate and Gift Taxes -- the Marital Deduction

A baseline policy of the federal estate and gift taxes is to tax wealth once every generation. For that reason, transfers from one spouse to another are made deductible, and therefore not taxed--subject to some important qualifications. You'll often see this referred to as the "unlimited marital deduction."

The unlimited marital deduction applies to any outright transfer to a spouse, and any transfer in trust where the assets of the trust will be included in the spouse's gross estate, and subject to tax, at the spouse's death. Before 1988, there were three trusts that qualified for the marital deduction:

The response to this was the "qualified terminable interest property" election added to the tax code in 1988, which is nicknamed "QTIP.". To qualify for the QTIP election, a trust must meet three criteria:

One last little detail: the marital deduction is only available if the spouse is a U.S. citizen. For non-citizen spouses, there is still a marital deduction of sorts, but the rules are a lot more complicated. We'll discuss that topic in our next installment.

The unlimited marital deduction applies to any outright transfer to a spouse, and any transfer in trust where the assets of the trust will be included in the spouse's gross estate, and subject to tax, at the spouse's death. Before 1988, there were three trusts that qualified for the marital deduction:

- Any trust where the spouse has a lifetime right to income and a "general power of appointment"--a right to withdraw assets from the trust, or direct them to his estate or creditors at death. Often called a "life estate plus power of appointment" trust, this was the most common arrangement.

- A trust where the spouse has a lifetime right to income and the property passes at the spouse's death to charity. (In this instance, there will be no tax on the second death because the property will qualify for a charitable deduction.)

- An "estate trust," which accumulates income while the spouse is living and pays it to her estate at death. These were used as investment vehicles back in the days when trusts paid income taxes at much lower rates than individuals. In about 20 years of private practice, I have yet to encounter one.

The response to this was the "qualified terminable interest property" election added to the tax code in 1988, which is nicknamed "QTIP.". To qualify for the QTIP election, a trust must meet three criteria:

- The spouse must receive all of the income of the trust while living.

- The trust may not have any other beneficiary while the spouse is living.

- The estate must make a "QTIP election" on the estate tax return.

One last little detail: the marital deduction is only available if the spouse is a U.S. citizen. For non-citizen spouses, there is still a marital deduction of sorts, but the rules are a lot more complicated. We'll discuss that topic in our next installment.

Wednesday, July 6, 2011

Federal Estate and Gift Taxes -- the Gross Estate

The federal estate tax is a tax imposed on the "privilege" of transferring property at death. Because it's imposed on transfers of property, it taxes more than just the property in your probate estate. The "gross estate," as we call it, consists of the probate estate, plus all sorts of arrangements that are intended to avoid probate, such as:

- Joint and survivorship assets.

- Payable-on-death and transfer-on-death assets.

- A revocable trust.

- Any irrevocable trust you've created, if you retain control over the disposition of wealth at your death--what we sometimes call a "taxable string" power--either as trustee or by some other means.

- Retirement accounts and annuities with a death benefit or survivor benefit.

- Assets which you have technically given away, but retain the right to use during lifetime. The classic example of this is a life estate in real property.

- Assets whose disposition you control through a power of appointment, but only if that power lets you appoint the assets to yourself, your estate, or your creditors. Powers of appointment have a lot of uses in sophisticated estate planning, and we'll go into detail about how they work in a future post.

Friday, July 1, 2011

Breaking News: Ohio Estate Tax repealed!

The Ohio estate tax will disappear on January 1, 2013, under a provision of the Ohio budget bill singed into law yesterday by Governor Kasich.

Only 22 states still have some sort of death tax, and the Ohio tax has the lowest exemption amount of any of them. It hits any estate in which $338,333 or more will be passing to beneficiaries other than a surviving spouse. This means that a lot of middle class families and small business owners end up paying an estate tax in Ohio who would not have to worry about it in most other states. Eliminating the tax will simplify the process of settling estates for Ohio families who aren't affected by the federal estate tax.

Read more about recent changes in state estate tax laws here.

Only 22 states still have some sort of death tax, and the Ohio tax has the lowest exemption amount of any of them. It hits any estate in which $338,333 or more will be passing to beneficiaries other than a surviving spouse. This means that a lot of middle class families and small business owners end up paying an estate tax in Ohio who would not have to worry about it in most other states. Eliminating the tax will simplify the process of settling estates for Ohio families who aren't affected by the federal estate tax.

Read more about recent changes in state estate tax laws here.

Wednesday, June 22, 2011

Federal Estate and Gift Taxes - an Introduction

The federal estate and gift taxes--we sometimes call them "wealth transfer taxes"--are the reason for much of what I do for my higher net-worth clients. These taxes have gotten a lot of attention and debate time among pundits and politicians recently, and we're going to be talking about them a lot on this blog. This post is the first in a series on how these taxes work, and what you can do to minimize their impact on your family.

The stated policy purpose of the wealth transfer taxes is to prevent the creation of large concentrations of inherited private wealth. The tax is therefore supposed to be paid only by "the wealthy." There's a never-ending debate over whether this is a proper thing for the government to be taxing in the first place, and whether it's not so much a tax on dynastic wealth as it is a tax on upward mobility--but all I want to talk about on this blog is how the taxes work, and how good estate planning responds to them.

While the estate tax is imposed on any transfer at death, and the gift tax on any transfer during lifetime, the Internal Revenue Code gives you a "unified credit" which cancels out the tax on a certain amount of wealth being transferred. We usually talk about the "exemption equivalent" amount that is protected from the credit, rather than the amount of the credit, because it's easier for clients to understand. However you want to think of it, if the wealth that you have to pass on to the next generation is less than the exemption equivalent, the federal wealth transfer taxes aren't an issue you need to worry about. (The Ohio estate tax might be, butthat's another topic for another time only if you die before January 1, 2013.)

Right now, the exemption equivalent is $5 million, but that could change in a very taxpayer-unfavorable way at the end of next year. We'll go into why that is in a future installment.

There are a couple of other mechanisms that provide relief from the estate and gift taxes. The policy of the current estate tax is to tax accumulated wealth once per generation, so transfers between spouses are accorded a "marital deduction" and are thereby not taxed. Also, mostly for administrative convenience, you are allowed a certain amount of gifts each year, the "annual exclusion," which are not counted for tax purposes. The annual exclusion is $13,000 per recipient per year, and that number is adjusted for inflation from time to time.

In our next installment, we'll talk about what gets included in an estate for estate tax purposes.

(Updated in response to the repeal of the Ohio estate tax effective 1/1/13.)

The stated policy purpose of the wealth transfer taxes is to prevent the creation of large concentrations of inherited private wealth. The tax is therefore supposed to be paid only by "the wealthy." There's a never-ending debate over whether this is a proper thing for the government to be taxing in the first place, and whether it's not so much a tax on dynastic wealth as it is a tax on upward mobility--but all I want to talk about on this blog is how the taxes work, and how good estate planning responds to them.

While the estate tax is imposed on any transfer at death, and the gift tax on any transfer during lifetime, the Internal Revenue Code gives you a "unified credit" which cancels out the tax on a certain amount of wealth being transferred. We usually talk about the "exemption equivalent" amount that is protected from the credit, rather than the amount of the credit, because it's easier for clients to understand. However you want to think of it, if the wealth that you have to pass on to the next generation is less than the exemption equivalent, the federal wealth transfer taxes aren't an issue you need to worry about. (The Ohio estate tax might be, but

Right now, the exemption equivalent is $5 million, but that could change in a very taxpayer-unfavorable way at the end of next year. We'll go into why that is in a future installment.

There are a couple of other mechanisms that provide relief from the estate and gift taxes. The policy of the current estate tax is to tax accumulated wealth once per generation, so transfers between spouses are accorded a "marital deduction" and are thereby not taxed. Also, mostly for administrative convenience, you are allowed a certain amount of gifts each year, the "annual exclusion," which are not counted for tax purposes. The annual exclusion is $13,000 per recipient per year, and that number is adjusted for inflation from time to time.

In our next installment, we'll talk about what gets included in an estate for estate tax purposes.

(Updated in response to the repeal of the Ohio estate tax effective 1/1/13.)

Monday, June 13, 2011

Retirement Assets Payable to an Estate

Qualified retirement assets, like traditional IRAs and 401(k)s and ESOPs and pension accounts, usually have a death beneficiary designated. This allows them to pass outside of probate. If the beneficiary is a surviving spouse, the spouse can "roll over" the assets into her own IRA and defer taking distributions until her "required beginning date." Other individuals, or trusts which are designed to qualify as "designated beneficiaries," have to start taking distributions the following year, but they get to stretch the distributions out over their life expectancy. This deferral is important because distributions out of an IRA or other retirement account are taxed as ordinary income for the year you receive them, and assets that aren't distributed yet continue to grow tax-free.

So what happens if the account owner didn't designate a death beneficiary? This happened in an estate I'm just finishing up. The decedent was a relatively young gentleman who never got around to doing any estate planning--no will, no death beneficiary designations--"no nothin'," as they sometimes say. Because there was no death beneficiary on his pension account, it became payable to his estate by default.

He had two heirs who each got a 50% share of the estate. Due to the peculiarities of how qualified plan distributions work, the pension trustee could not make distribution straight to the heirs. The estate had to first open an IRA account. The pension plan made a "direct transfer" to the estate IRA. The heirs each opened an individual IRA, and the estate immediately transferred the assets in equal shares to their accounts.

Because the pension plan did not have a "designated beneficiary," the heirs are required to take distribution of the IRA within five years. This isn't as good as taking it out over one's life expectancy, but at least they can get some deferral.

So what happens if the account owner didn't designate a death beneficiary? This happened in an estate I'm just finishing up. The decedent was a relatively young gentleman who never got around to doing any estate planning--no will, no death beneficiary designations--"no nothin'," as they sometimes say. Because there was no death beneficiary on his pension account, it became payable to his estate by default.

He had two heirs who each got a 50% share of the estate. Due to the peculiarities of how qualified plan distributions work, the pension trustee could not make distribution straight to the heirs. The estate had to first open an IRA account. The pension plan made a "direct transfer" to the estate IRA. The heirs each opened an individual IRA, and the estate immediately transferred the assets in equal shares to their accounts.

Because the pension plan did not have a "designated beneficiary," the heirs are required to take distribution of the IRA within five years. This isn't as good as taking it out over one's life expectancy, but at least they can get some deferral.

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Probate and How to Avoid It

Many clients come to me wanting, among other things, to "avoid probate"--that is, to avoid having assets in their estate administered in the probate court. There are several reasons why you might want to do this:

- Privacy is the biggest reason: anything that gets filed in probate court, including an inventory or account showing the value of assets, is part of the public record and accessible to everyone.

- In Ohio, where I practice, assets in a probate estate are subject to the claims of creditors of the deceased, while most non-probate assets are not. This is not true in some other states.

- Probate administration is a slow-moving process, and keeping assets out of probate often permits them to be distributed faster. This is not necessarily true in large estates, where the preparation, filing, and possible auditing of the federal estate tax return is usually the most important factor determining the speed of distribution.

- Things you've given away before you die are not probate assets because, well duh!, you no longer own them at death.

- Property in a revocable trust is owned by the trustee, and not by you individually. Even if you are serving as your own trustee, you hold the trust property in a fiduciary, not individual, capacity. So long as the trust document tells us what to do with the property when you die, the trust will not be a probate asset.

- What you have saved in a retirement plan account or IRA is technically owned by the plan trustee or IRA custodian in trust for your benefit. Like the revocable trust corpus, it will not be a probate asset so long as you've named a beneficiary.

- If you have insurance on your life, it doesn't matter whether you own the policy or someone else does--so long as you've designated a death beneficiary, the proceeds will not go through probate.

- Real estate held in a joint & survivor or survivorship tenancy, or for which you've designated a transfer-on-death beneficiary, does not go through probate because title passes by operation of law at your death.

- Securities or bank accounts titled “joint & survivor” or which have transfer-on-death beneficiary designations, do not go through probate either, though in this instance it's because title passes by contract (the account agreement with whatever institution you're dealing with) rather than operation of law.

- Property interests which terminate at death do not become part of the probate estate because the property no longer exists. Examples of this would be an old-style pension that pays you an annuity for life, but has no death benefit.

Wednesday, June 1, 2011

Intestate Succession

What happens if someone dies "intestate"--that is, without having made a will? Who gets their property?

The answer is provided by something called the "statute of descent and distribution." This law tells us what to do with a deceased person's property. It's the legislature's attempt to guess what the deceased would have wanted if he or she had been asked the question or had bothered to tell us, and it's not an unreasonable guess in most instances. The people who take under the statute of descent and distribution are known as "heirs at law" or, in some situations, "next of kin."

We'll take a look at how one such statute works after the jump.

The answer is provided by something called the "statute of descent and distribution." This law tells us what to do with a deceased person's property. It's the legislature's attempt to guess what the deceased would have wanted if he or she had been asked the question or had bothered to tell us, and it's not an unreasonable guess in most instances. The people who take under the statute of descent and distribution are known as "heirs at law" or, in some situations, "next of kin."

We'll take a look at how one such statute works after the jump.

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

What is a Trust?

Trusts are a common estate planning device, but many people (including a few lawyers!) don't completely understand what one is. We’ll start the discussion with a definition of a trust that I've used in several CLE presentations I've given:

A trust is a relationship created by a grantor who transfers legal title to property (known as the trust corpus or trust principal) to a trustee, who holds it as a fiduciary for the benefit of one or more beneficiaries. The beneficiaries’ rights of enjoyment are set forth in the terms of the trust, which are usually contained in a governing document (which may be called a “Declaration of Trust” or “Trust Agreement” or a “Declaration and Agreement of Trust” or sometimes just a “Trust.”)There are several important concepts contained in that definition:

- A trust is a fiduciary relationship between the trustee and the beneficiaries, not a separate legal entity (person) like a corporation or LLC.

- Since the trust is a relationship and not an entity, legal title to the trust corpus is held by the trustee. While we often casually speak about "the trust" doing something (conveying property, making a distribution, or so on) as if it were an entity, it's actually the trustee who is the actor.

- Since the trustee is a fiduciary for the beneficiaries, it naturally follows that beneficiaries are the persons with standing to enforce the terms of the trust—that is, they’re the ones who sue the trustee when the trustee fails to follow the terms of the trust.

- Clearly identify the parties to the trust: the grantor, trustee, beneficiaries, and any trust advisors.

- Indicate if the trust is revocable or irrevocable, and identify who may hold powers to amend the terms of the trust (reserved powers to amend; powers of appointment).

- Clearly set forth the dispositive (enjoyment) terms of the trust (including those circumstances where the distribution is subject to review or approval by a trust advisor or other outside party) so that the trust accomplishes the grantor’s objectives.

- Provide a mechanism for succession in the office of trustee.

- Confer powers on the trustee to permit him to efficiently manage the trust. While the dispositive provisions of every trust--who gets what, when--will be unique, basic trustee powers and other “administrivia” will not vary much from document to document. (The Ohio Trust Code has a nearly-comprehensive set of statutory trustee powers which drafters may incorporate by reference, and most of us who practice in this area have standard language we use for nearly every trust document. Some trust companies have their own standard trustee power language which they will require in the document as a condition of accepting the trust.)

- Do all of these things with sufficient clarity that both the trustee and the beneficiary can understand what the trustee is supposed to do and who receives what without having to ask a judge to construe or interpret the document.

Monday, May 30, 2011

Fiduciary Duty

The terms "fiduciary" and "fiduciary duty" get used a lot in estate planning. The legal term "fiudciary" derives from the Latin words fides, meaning "faith", fiducia, meaning "trust," and fiduciarius, meaning "holding in trust." As a generic term, a "fiduciary" is a person who has ownership or control of property for the benefit of someone else.

A trustee owns title to the property in a trust, but holds it for the benefit of the trust's beneficiaries, not himself. We would therefore say that the trustee is a fiduciary over the trust property. While a trustee is the classic example of a fiduciary, there are others: the executor or administrator of an estate is a fiduciary with respect to the estate; a guardian is a fiduciary with respect to the property of the ward (person under guardianship); an agent under a power of attorney is a fiduciary with respect to the property of her principal; and the officers and directors of a corporation are fiduciaries with respect to the corporation's assets (which are owned by the shareholders).